The BRIEF TRAP

When saying “yes” is the most dangerous decision

From execution to strategic product consulting

There is a situation that happens more often than many designers would like to admit, especially in the home appliances industry.

A brand contacts you to develop a new compact espresso coffee machine.

The brief sounds simple:

very small, low cost, premium look.

“We’ve seen your work, we want that level of detail.”

So far, everything seems straightforward.

Then the real constraints emerge: limited tooling budget, low-cost plastics, tight timelines.

Yet the expectation remains that the product should look and feel high-end.

This is where many projects start to drift off course.

Not during the design phase, but before it even begins.

The hidden risk behind “ok, I’ll try”

Accepting the brief without questioning it may look collaborative.

In reality, it is often the biggest mistake.

The risk is not just ending up with a weak product.

The real risk is spending months on a project that will later be diluted, simplified or cancelled because the initial expectations were never realistic in relation to production constraints.

For this reason, in real-world industrial design, the most critical phase is not concept development, but the first meeting.

The real question to ask

The issue is not:

“How do we make cheap plastic look premium?”

The real question is:

how willing is the client to reconsider their priorities?

Only after this point is clarified does it make sense to talk about solutions.

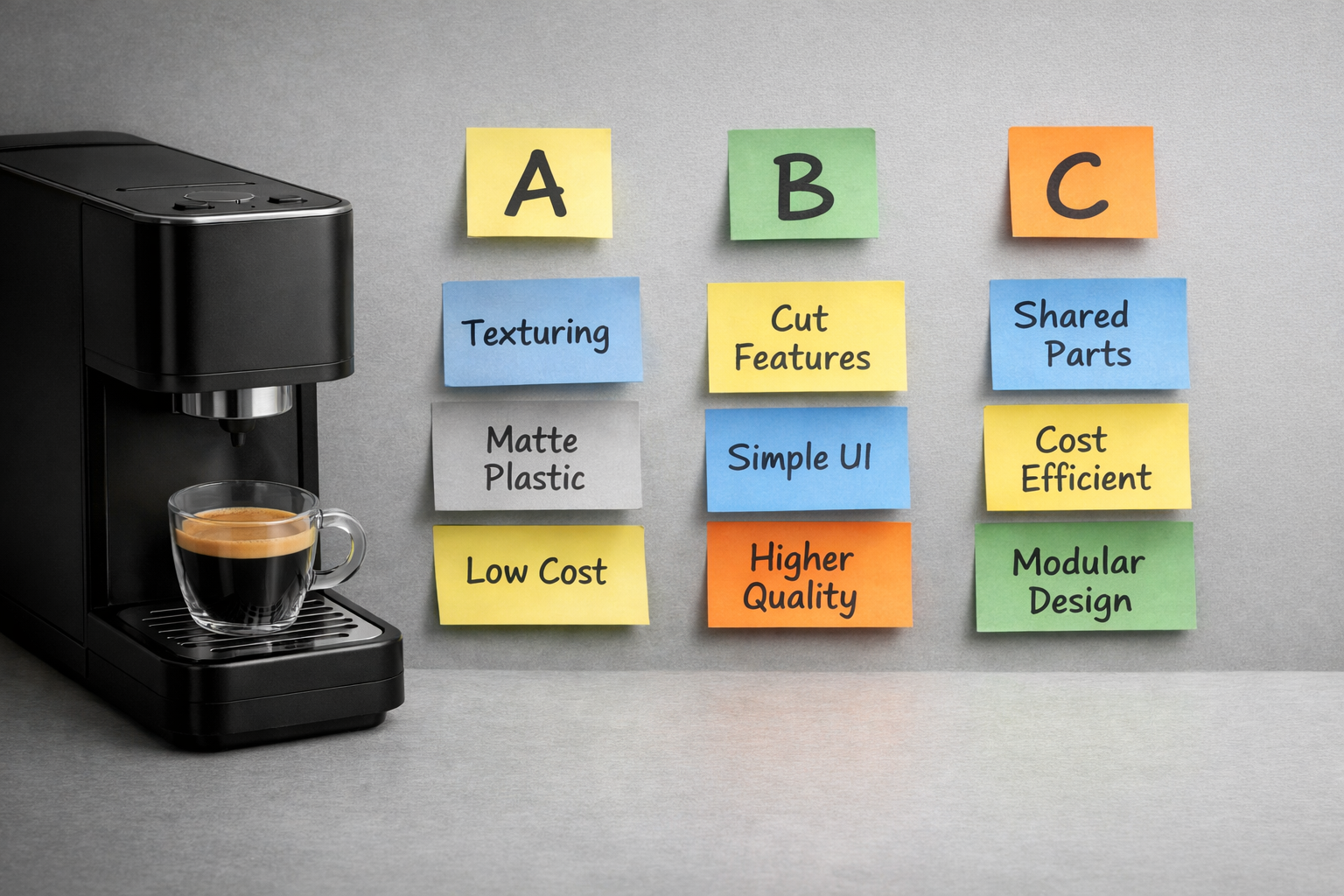

Three possible approaches (all legitimate)

When facing this kind of brief, there are several possible paths. None is universally right, but each has very clear consequences.

A. Textures and finishes

This is the approach of the technical virtuoso.

Using textures, micro-grain surfaces, sparkle finishes or matte treatments can help hide typical defects of low-cost plastics and improve perceived quality without increasing cycle costs.

From an injection molding perspective, it is a solid and technically sound solution.

Advantage:

You solve the problem without creating friction with the client.

Limit:

You stay within the role of the executor. The brief remains untouched.

B. Reducing features to increase quality

This is the approach of the product strategist.

Here you are not refining the brief, you are challenging it.

You are saying that with this budget, you cannot win on every front. A choice has to be made.

Is it better to have an essential, coherent machine focused on coffee quality, or a product full of features that only look premium on paper?

Advantage:

You position yourself as a partner who cares about the commercial success and brand reputation.

Risk:

It requires strong negotiation skills and the ability to argue beyond form and aesthetics.

C. Rethinking the product architecture

This is the approach of the system thinker.

Shared components, existing platforms and already industrialized solutions can free up budget to invest where users actually perceive value: enclosure quality, interface clarity, overall build.

It is often underestimated, yet extremely effective.

The real step forward: using technique to support strategy

The transition from senior designer to strategic consultant happens when you learn to use technical competence to support business decisions.

Many clients, especially non-technical ones, believe that adding a feature costs very little.

You know that every extra display, LED or button means:

more complex tooling

additional wiring

longer assembly times

more expensive PCBs

more potential failure points in production

At this point, design stops being about form and becomes the ability to make invisible costs visible.

How to talk to a CEO (a realistic example)

At this stage, saying “it’s better this way” is not enough.

You need to translate design choices into risk, margins and positioning.

A sentence that works could be:

“With this budget, adding those extra features pushes us toward borderline components and more complex assembly. That increases production risk and potential returns. If we simplify, we can rely on proven components, reduce risk, and protect your margins.”

At that moment, design is no longer an opinion.

It becomes a strategic decision.

In industrial design, many problems are not formal or technical.

They are problems of expectations, priorities and vision.

Setting the first meeting correctly means avoiding months of wasted work and increasing the chances that a product reaches the market with coherence and quality.

Design is not about making something look premium at all costs.

It is about making conscious decisions within real constraints.

That is where the role of the designer truly changes.